The twelfth entry in Westlake’s Parker series, The Sour Lemon Score (1969) is also the last of the “Score” books to debut as a Gold Medal paperback. The “sour lemon” choice for the title (assuming it was the author’s choice this time) implies a return to a more orthodox form, without much involvement by his girlfriend Claire and starting off with a well-planned but vanilla bank robbery. This departure from the crazy quilt being stitched by The Rare Coin Score, The Green Eagle Score and The Black Ice Score appears to have made TSLS a more popular book–and maybe the most highly regarded of the Gold Medal issues.

The plot of TSLS recalls that of another widely appreciated Parker title: The Seventh. That novel began in the aftermath of a successful heist; Parker returned to his hideout from shopping to find his girlfriend impaled by a sword and the suitcases of money missing. Parker then spends the rest of The Seventh hunting down the nameless young man responsible, attaining bloody retribution after much difficulty. TSLS follows a similar path with a bank heist and double-cross, but this time the perpetrator has a name–George Uhl–and life history that Parker learns as he plays detective.

Still, you cannot go home again: TSLS features a Parker confronting a generation gap within his loose network of underground figures. He’s losing his trusted associates to death or retirement and left with a cast of increasingly younger and less predictable individuals. It also ends in a violent, surreal sequence in that most reliably surreal setting of Parker’s world, the suburbs.

Allison & Busby edition. www.existentialennui.com

In a speech reproduced in The Getaway Car, Westlake argued that American private-eye fiction used Westerns as inspiration, more so than traditional English mysteries. Starting with a bank robbery and bloody shootout, TSLS pays tribute to the Western genre: much of the book is Parker, guns in pockets, hunting down Uhl across the tri-state* area. Instead of horse, he rides a used green Pontiac (despite the Allison & Busby cover).

the bad

Parker and Uhl are half of a four-man robbery crew, with the other to being an experienced (but never arrested) criminal named Andrews and Benny Weiss, another old hand in the business for thirty years. Weiss is responsible for recruiting Uhl as the getaway driver.

Parker knows Andrews to be very skilled at disguising his face with theatrical makeup, as well as career-long streak of jobs pulled without any arrests. This clean record is a concern for some in the underworld, but Parker only cares about Andrews’ reputation for doing the job. On the other hand, Parker notices how agitated Uhl is while they wait in the car:

Parker turned sideways in the seat, facing Uhl, so he could see everybody. “The question is,” he said, “is George going to spook?”

Uhl looked at him in astonishment. “Me? Why?”

Weiss said, “Parker, of course not. George is okay.”

Andrews said “What’s wrong?”

Parker told him, “George is being nervous.”

Uhl said, “You aren’t nervous?”

“My face is dry,” Parker said.

. . .

“I don’t want to come out of that bank,” Parker said, “and find no car.”

Uhl said angrily, “What are you talking about? You think I’m an amateur, for the love of God? I’ve driven half a dozen times. I drove for Matt Rosenstein–you think he’d take a chance on somebody?”

That “my face is dry” statement is the only time Parker directly responds to Uhl in the chapter, and even then it seems as if he’s addressing the entire crew. Notably, Uhl takes the bait and divulges another name (Matt Rosenstein) as a prior connection. The conversation continues with Parker watching Andrews while Andrews studies Uhl’s face. Once Andrews decides that Uhl just has temporary stage fright, they proceed with the plan.

Later, Parker does ask Uhl about using a grenade for the armored car they’re targeting, and Uhl tries to convince Parker that his jitters have passed. Too concerned with his plan of action, Parker compartmentalizes his instinctive doubts about the driver and helps rob the bank. The heist goes off without a hitch, with Uhl setting off the smoke-grenade and then driving the crew (and the bank’s lockbox of cash) out of the city.

Everybody was done working now but Uhl, and Uhl had rehearsed his part so often that he could almost do it asleep. Right at the corner, left at the alley halfway down the block, right at the next street, and then four blocks straight.

. . .

Uhl, relaxed at the wheel now, glanced in the rear view mirror and said, “Shoot the lock off. Let’s see how much it is.”

“When we get to the farm,” Parker said.

“Why not now?”

Weiss, up front with Uhl now said, “George, you want a bullet ricocheting around in the car? Where’s your sense?”

So Uhl is competent when following a plan, but lacks judgement when confronted with a novel situation. These traits manifest again once Uhl gets them to a farmhouse and the money is being counted. Seeing the crew distracted with the cash, he pulls his gun and shoots Andrews in the head. Parker manages to escape through a window, but Weiss is also killed and the farmhouse set on fire. Uhl leaves with the car and loot, of course, but after sending a few bullets after Parker, he abandons the idea of hunting him down in the nearby woods.

Coronet edition. www.existentialennui.com

Uhl had been plotting and anticipating his ambush for years, waiting through various jobs for the right situation. However, he failed to shoot the most dangerous man first, leaving Parker alive. We learn throughout TSLS that Uhl has left a whole string of associates and girlfriends who know both his real name and his criminal activities, something which Parker and other veteran thieves have been careful to limit.

the good

Of course, two of these veterans–Andrews and Weiss–are left dead and Parker has to walk back into civilization. Fortunately, Claire (in her only role in the book) is in New Orleans to wire him money, so Parker manages to resume his pursuit of Uhl, and the tale from the robbery, in short order.

Uhl’s reckless flight is placed in contrast with Parker’s methodical detective work. He’s not burning with hatred for Uhl, but wants his money and anticipates having to kill for it. This leads to a purchase of two nearly identical “Terrier” revolvers from the back room of an antique store:

He went with her down the narrow aisle between the seatless chairs, the cracked vases, the chipped enamel basins, the scarred chifferobes. Everywhere there was frayed cloth, cracked leather, sagging upholstery, chipped veneer, and an overall aura of dust and disuse and tired old age.

The proprietor of the store, and de facto gun dealer, is a relative (or widow) of Mr. Dempsey, whom Parker had used before knew of from a former associate. Dempsey has passed away, leaving this elderly woman in charge of the “special stock.” During the purchase, Westlake imparts her with significantly more dignity than the aged furniture:

“A hundred for the two,” he said. He put the guns back in their shoeboxes and reached for his wallet.

“That’s fine, then,” she said. “I’ll go get the shells.”

She went away and got the shells, and when she came back Parker had two fifties in his hand. She handed him the shells, and he handed her the money. She thanked him and said, “You know, I’d rather you didn’t load them in the store here.”

“I wasn’t going to.”

“That’s fine. Shall I put some string around the boxes?”

“Yeah, do that.”

She put the lids on the boxes and started to carry them away, but Parker said, “Bring the string here, why don’t you?”

She looked surprised. “Oh, I see! Of course.” She went away, came back with a roll of twine, and said, “I wouldn’t give you empty boxes. Sooner or later you’d just find out and come back. And where else do I have to go but here?” She tied the two boxes together while she talked. “That’s the one kind of person you can trust,” she said. “The person who doesn’t have any place to go.”

Her final statement is reinforced by another interaction Parker has after checking into The Green Glen Hotel outside of Scranton, Pennsylvania. The proprietor there is a trusted retired prostitute named Madge, who acts a trusted social maven in the loose network of professional thieves.** Not only does she know Parker by his name and underground associates, but she notifies him of money kept there for him, the proceeds from a successful jewelry heist (described in The Outfit).

Parker makes a call to his old friend Handy McKay, who has retired from crime and just asks that Madge send him his share of the cash. More importantly, Madge tells Parker about Matt Rosenstein, the man George Uhl had told him about while defending his credentials as a getaway driver.

Her expectant look faded slowly. “Uhl? George Uhl? He must be new.”

“Pretty new. He’s worked six times, he said. He said one time he worked with Matt Rosenstein. The way he did it, Rosenstein should be hot stuff, bit I never heard of him.”

“No, you wouldn’t,” she said. “Matt Rosenstein, I know him. You wouldn’t ever cross his path. You two have different kinds of outlooks.”

Later in the story, Parker visits Benny Weiss’ home, to learn if he had ever shared information about George Uhl with his wife (now widow). Weiss had guaranteed Uhl to Parker and Andrews, so he figures Mrs. Weiss could have had some familiarity with him. This also means that Parker is the one who tells her that Benny is dead. Her reaction is given an unusual stylistic treatment for a Richard Stark title:

Turning her back to him to start the coffee, she said, “You being here is bad news, I suppose. You being here, Benny not being here.”

“Yes.”

“He’s dead, I suppose.”

“Yes.”

She sagged forward for a second, her hands bracing her against the counter. He watched her, knowing she was trying to be stoic and matter-of-fact as she could, knowing she would hate him to do anything to help her unless she was she was actually fainting or otherwise breaking down, and knowing that she had to have rehearsed this moment for years, ever since the first time Benny had gone away for a month on a job. Like Claire, Parker’s own woman. Rehearsing the way she would handle it when she got the news. If she got the news. When she got the news.

The mention of rehearsals in this case is an interesting reference to theater, like Andrews’ ability to disguise his face for bank jobs. Mrs. Andrews knows who Parker is talking about, but–in a testament to their ability to keep Benny’s criminal life compartmentalized–knew him only as “George.” After composing herself, she negotiates a payout for calling Benny’s connections about Uhl, acting as if he were still alive. She gets Parker to admit that he’s not out for personal revenge, only the money from the heist (maybe like Claire, Parker’s own woman).

the ugly

Perfectly competent in using the trust built up in his own network to track Uhl and Rosenstein, Parker continues to show a blind spot for the his targets’ cunning. Before leaving Madge and the Green Glen Hotel, Parker has Handy McKay call around and learns that Rosenstein shares an apartment with a record store manager named Brock.

As openly homosexual as a character one might expect to find in 1969, Brock is another younger, deceitful personality outside of Parker’s experience. He forces the cashier of the record store to call Brock, and arranges a meeting at his apartment to talk about Rosenstein. Brock does not make much of a dangerous impression with his attempted small talk and affectations, but he slips a drug into Parker’s coffee.

Brock isn’t in the room when Parker feels himself going under, so the thief manages to hide his two guns inside the couch cushions before hitting the floor. The guns seem to embody the more mythical, movie-reel aspect of the story, both in this case and in the final shootout. Getting involuntarily drugged is a familiar plot device in 1960’s genre fiction, and as expected, Parker gets interrogated about Rosenstein (probably by Rosenstein) before ending up in an alley across town.

The drug Parker experiences is a short-acting barbiturate of some kind, possibly sodium thiopental or sodium pentobarbital. In theory, it inhibits the cognitive facilities one needs for active deception before unconsciousness:

“Is Rosenstein the only lead you have?”

“Yes.”

“Do you have any other business with Rosenstein?”

“No.”

“Are you a threat to Rosenstein?”

“No.”

“Can you find Uhl if Rosenstein won’t help you?”

Hard question. Irritation. Pain.

Parker is able to recover his senses, and eventually his guns, but other characters in Rosenstein’s path are not so fortunate. Rosenstein decides to find Uhl and the cash for himself, and embarks on his own pursuit. Where Parker plays a decent private detective, Rosenstein is a sadistic torturer: the second half of TSLS becomes tough reading when Rosenstein finds Uhl’s Washington girlfriend.

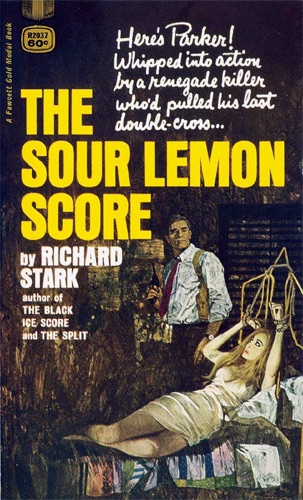

Robert McGinnis cover for Gold Medal edition. http://www.existentialennui.com

The McGinnis cover depicts Parker standing over another girlfriend of Uhl’s, this one in New York. Previously used by Uhl, she was initially cooperative with Parker, but eventually her loyalties switched and she had to be left tied up on her own couch. The possibility that Parker is a true sociopath, as asserted in various reviews (including the Dennis Lehane forward of the University of Chicago edition), is addressed in his actions with the female characters. Rosenstein shows what a monster is capable of.

Parker also visits the girlfriend in Washington (too late, this time), as well as the house of another older associate of Uhl’s. This one is a man named Pearson, connected to Uhl and Weiss, and identified by Weiss’ widow. Pearson is living comfortably from his ill-gotten gains, but like Parker and Weiss, underestimates how dangerous Uhl is: he calls Uhl after Grace Weiss called him.

[Pearson] “That’s why Grace called, huh? To get Uhl’s address for you.”

“Yes.”

“So now you’re coming to me direct,” Pearson said, and then he said, “uh,” and a small black thing appeared in the middle of his forehead, making him look cross-eyed.

The ending involves a final, violent confrontation in a suburban home, where an old acquaintance of Uhl’s is living. I imagine the intent was to follow the conventions of a Western, but it certainly plays out like an advertisement for supporters of the Second Amendment. It reminded me of James Garfield’s Death Wish, clearly intended to be more about grief than vengeance, but the popular takeaway message ending up as something else.

The have-gun, will-travel narrative of TSLS is a definite change from the Shakespearean intrigue of The Black Ice Score, and Parker’s actions are more conventional. It struck me as a bit less ambitious, but I cannot discount the fact that TSLS was a one-sitting read. Fans of the series will, as always, find compelling actions, as well as much to appreciate in the moments between the violent turning points. 7/10.

* The tri-state area in this case being New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Washington, D.C.

** Westlake describes Madge as someone who, in her own way, contests the passage of time. See the 2-part article in The Westlake Review for more discussion of Madge, the Terrier pistols and the car (among other things).

This is a hard one to figure, and definitely put me through my paces when I reviewed it. It exemplifies Stark’s habit of putting Parker to the question–“If you are in this situation, what will you do?” There are quite a few questions of that nature in the book.

I wouldn’t say Parker was burning with hatred for Uhl, but it’s made very clear that he is immovably set on killing the guy. His first priority is the money, but no amount of money gets Uhl off the hook. Parker has to get him. Then he has him–and things don’t work out as expected. I think Jack French (from The Rare Coin Score) would say this is really unfair.

It’s never about hate. Parker kills because of an compulsion created by certain types of human behavior. It triggers his hunting instinct, and when Parker is hunting you, you’d better go underground. Like twenty miles underground in a lead-lined bunker should do it. Maybe.

I didn’t see the western angle–showdown at the suburban corral? Again, the two gun thing is drawn from Hammett. There are some shared tropes in the western and crime genres (since westerns are often about crimes).

The idea is to put Parker in a situation where he (once again) demonstrates to us that he doesn’t kill except in very specific circumstances. He just wanted the money. The money’s gone. Rosenstein and Brock are no longer a threat (for the moment). He was never after them. They didn’t sour one of his heists, like Uhl did. They didn’t have a working relationship with him to betray.

Second Amendment? Parker never owned a legal gun in his life. He wouldn’t see the point.

After The Black Ice Score, there probably was some pressure to go back to more familiar story ideas–and skin hues–but in many ways this is a much stranger story. Parker at his most unaccountable. And dealing with two of his most strangest adversaries in Rosenstein and Brock.

Parker is acting in the role of a hardboiled dick here, yeah.

But decent? I don’t think so. He’s not sick in the soul, like Rosenstein. No sadism in him. No self-deception. Different outlooks. Madge was right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, my 2nd Amendment chatter was referring to the fact that the Pennsylvania homeowner was defenseless against the likes of Rosenstein and Brock: he appeared inadequate and even irresponsible. I’m not taking a position here, but the message of that sequence was pretty clear–if you mix with criminals, even unintentionally or for old time’s sake, you have to have the means to defend the castle. That might not be the author’s intent, and neither was it the intent of Garfield’s novel, but once it’s on paper it speaks for itself.

The odd choices Parker makes at the end, sparing the lives of Rosenstein, Brock and Uhl, but leaving them to some kind of frontier justice, speaks to the influence of the Westerns, I think. Also, the very unlikely way he charges in with pistols blazing at the end, and not getting seriously wounded. Maybe it is all done in reference to Hammett, but I haven’t read the right Hammett to make that claim. So, it’s Two-Guns Parker on his Steel Horse for the time being.

LikeLike

Oh no, I don’t get that at all. Those guys came calling at his home because he got himself involved in stuff he had no business messing with, because he was bored with his safe suburban life, and wife. Not because he didn’t buy a gun. Which Rosenstein would have just used on him anyway. While Brock watched, making upset noises. There is a moral there–a Starkian moral, which invariably translates to “Know who you are, know what you’re capable of.” Not “Go arm yourself.” Parker doesn’t walk around armed most of the time. Well, except for those hands of his.

It’s crime fiction. It is not mean to be realistic, but it does have a verite feeling to it that most stuff written in this vein does not. Because Stark makes it real, through the power of his writing. You get through the ride, and you think “Did that really just happen?” No, it’s just a damn good book.

Why does this bother you more than everything that’s happened with Parker before now? He defeated a nationwide criminal syndicate with one skinny sidekick and some letters!

I think it’s because this feels more real than that, and that makes you more inclined to look critically at it, but in point of fact there have been many instances (in war, for example) of one man shooting many while not being shot. Google ‘Sergeant York.’

Parker has already been shot multiple times in the series, and will be in the future. He lives because it’s series fiction, and he’s the main protagonist. Might as well ask why D’Artagnan doesn’t get a rapier in the heart, or a musket ball in his brain. He’s still alive at the end of three long books, though all his friends are dead (spoiler alert).

Again–good books. But for the record, there was a real D’Artagnan. Who was killed in battle, after a long distinguished military career. In his early 60’s.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_de_Batz_de_Castelmore_d%27Artagnan

LikeLike

“Most strangest.” I had actually been out drinking with friends, and it was late. And even so.

LikeLike

Slight correction–Parker had not been to that frowsy antiques shop before. Grofield had mentioned it to him as a place people living outside the law could go to equip themselves, and he happens to be in that general part of the country. Parker files away information like that in his head for when he’ll need it. The woman remembers Grofield well, such a charming man.

Honestly, if I was going to buy a gun, which I never will, this is how I’d want to do it. The Stark Way. Hobby Shop, seedy private detective, down on its heels antique store. Guy says if you don’t use the gun on the job, he’ll buy it back from you half-price (I’m pissed Parker never did this, such a neat perk. He has no respect for good customer service.)

What do they do now? Just walk into the gun store, or a convention hall crammed with weapons buffs, and just buy it. If you have some other shopping to do, you could just go to Walmart. Or hey, order online. Never have to leave the house. We ship the guns to you.

So. Boring.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Correction noted with the strikethrough format, the hair-shirt of the internet. I must have been thinking of the place in Buffalo Parker had visited in another book, maybe The Green Eagle Score.

This one definitely seemed to be darker than the other “..Score” titles. I thought maybe the two-guns thing contained some deep-seeded joke, but obviously I don’t know what’s specifically being referenced. Maybe two Chekov’s Guns?

LikeLike

There’s a family involved–a man, his wife, and three kids. Not all of them make it out alive. The survivors–well, that’s another book, but I don’t think we could call it a happy ending. Pretty dark, all right.

If I’m right, the two guns thing references Hammett. But honestly, he’s fighting two guys at once, so why wouldn’t he use two guns? It’s a cool image, that makes people feel like they got their sixty cents worth (I was actually alive when you could buy a book like this, with McGinnis cover art for sixty cents, and I missed it. “Mommy, can I have the book with the woman tied to a bed? Please?”)

Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

LikeLike