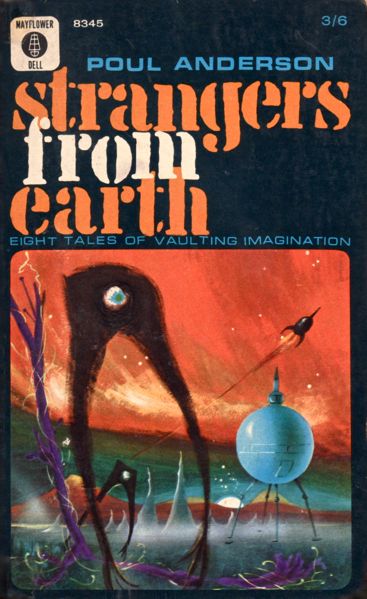

The Poul Anderson collection Strangers from Earth concludes with three more stories from the 1950s. In my first two reviews of this collection, I covered idea-driven pieces dominated by dialogue, and then action-driven stories that made their political and cultural points on more subtle level. Here, we get a mixture of these two types.

“The Star Beast” (1950)

Much is accomplished in the opening lines of this story:

The rebirth technician thought he had heard everything in the course of some three centuries. But he was astonished now.

“My dear fellow–” he said. “Did you say a tiger?”

“That’s right,” said Harol. “You can do it, can’t you?”

Harol, a dissolute citizen of a decadent, post-scarcity Earth, has once again become bored of his existence and has decided to undergo reincarnation. Rather than swapping races or sexes, he chooses to inhabit the body of a tiger. Rebirth in animal forms is a fashionable undertaking in Harol’s time, but not into nervous systems unsuited for human thought and emotion.

Reincarnation is a rich trope in vintage SF; this blog has encountered it before in Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light, and Philip Jose Farmer’s To Your Scattered Bodies Go has always been a personal favorite. Not to mention the “regeneration” episodes that tie together every incarnation of the titular character of Dr. Who. However, the focus of “The Star Beast” is not so much reincarnation is it is transfiguration into the form of another species. This too, has seen coverage here, in discussion of Michael Bishop’s “The White Otters of Childhood.” Incidentally, my enthusiasm for the work of Bishop started after finding this review of his novel Transfigurations, which I also recommend.

Perhaps the most bizarre aspect of the opening lines is the notion that someone–in organic form, no less–has spent a full three centuries as a rebirth technician. It’s difficult to imagine being in the same line of work for that stretch of time, but at least he’s not suffering redundancy like the two unemployed gentlemen in “Quixote and the Windmill” (see part 1).

Generations of this lifestyle has left the denizens of Earth satisfied but vulnerable to disruption. That disruption comes in the form of an invading fleet from a far-off colonial planet, headed by an admiral named Felgi:

“You left us in exile,” said Felgi, and now the wrath and hate were edging his voice, glittering out of his eyes. “For nine hundred years, Earth lived in luxury while the humans on Procyon fought and suffered and died in the worst kind of hell.”

This bitterness coming from neglect of an imperial authority is a major theme of Anderson’s Flandry series, specifically The Rebel Worlds and The Day of Their Return. Here, the Terran representative (a figurehead for the most part) is dumbfounded by the fact that the Procyonites would not simply want to share in the advancements that has made life on his planet so easy.

Met with practically no resistance, Felgi destroys the mechanical control centers and plunges Earth into a state of lawlessness. This makes his seizure of power nearly automatic, but the former Terran president Ramacan does manage a last, desperate heroic act to throw a wrench into Felgi’s ultimate plans.

Meanwhile, the transformation of Harol into a tiger is described in enthusiastic detail. Harol’s personality and memories fade against the intensity of different, keener senses and physical power:

At night, at night–there was no darkness for him now. Moonlight was a white, cold blaze through which he stole on feathery feet; the blackest gloom was light to him–shadows, wan patches of luminescence, a shifting, sliding fantasy of gray like an old and suddenly remembered dream.

Anderson goes on to quote the first verse of William Blake’s 1794 poem “The Tyger,” awkwardly putting it among Harol’s disappearing recollections. There are many interpretations of “The Tyger,” but here, the question What immortal hand or eye dared frame thy fearful symmetry? is posed about a futuristic, all-providing system of technology. Humans are now incapable of engineering their machines, instead understanding them as supernatural.* They lost their right to this existence, in favor of a more primal one.

“The Star Beast” is a crowded combination of intriguing ideas; Harol’s transfiguration into a tiger and the Earth/Procyon conflict would seem to have enough character arcs and angles to fill out a novella, at minimum. Instead, the invasion drama is played out in an extended conversation between two characters, and the pre-existing relationship between Harol and his longtime lover Avi is contained in another passage of dialogue. The action in between is interesting, and Anderson ends the story on a point of ambiguity, referencing the Frank R. Stockton’s “The Lady or the Tiger,” another piece famous for the question it asks. This is not quite a kitchen-sink effort, but some readers will not view this piece as more than the sum of its parts.

“The Disintegrating Sky” (1953)

This story is another one dominated by conversations between characters; it’s becoming evident that Anderson spent considerable time speculating what people in the future would say to each other. This means that some of his short stories can feel starved for action, but the practice has paid off in fleshing out the characters of his later novels.

Cliff Bronson, an affluent and well-connected bachelor, has an apartment in Manhattan where we occasionally invites friends and acquaintances to discuss high-mind topics. Because this is an early-1950s Poul Anderson story, all participants are well-dressed men who drink and smoke as they talk. This is just his way of clearing the stage for ideas without cultural, sexual or psychological differences to complicate things (this was kind of thing the early John Brunner was working to change within the genre, before it was fashionable to do so).

This is somewhere in the near future, where sophisticated men like Bronson stock their dwelling with cultural artifacts:

There were shelves of records, the old masters of music, and the walls were lined with well-worn copies of the world’s great literature, from Aeschylus to Guthrie.

But among the records were also to be found the sinister discords of Stravinsky and Berlioz along with the latest better popular releases. And some very curious and disquieting volumes nestled amongst Shakespeare and Goethe and Voltaire. Across the room Frans Hals’ sardonic Jester leered at a recent Dali. The arrangement seemed deliberate, perhaps symbolic.

Among Bronson’s guests is a nuclear scientist associated with “the latest nuclear bomb project,” brought to the party as entertainment for his regular armchair philosophers. Unfortunately, Cogswell has spent most of the night brooding in his armchair, apparently too occupied with the pressures of his work. Other guests (an executive and a sculptor, for what it’s worth) manage to engage him with a question about the nature of time.

“Why do we see time as flowing instead of static?” asked Gray.

Cogswell shrugged. “Who knows? We just do. Some authorities have suggested that the time-direction is the direction of the increase of entropy. But somehow I’ve never been satisfied with that theory, perhaps because it’s so vague.”

Burkhardt looked triumphant. “I say we move from past to future because the Author is writing all the time. . . The past is what he has already written.”

“And he never rewrites,” said Bronson with a wry smile. “The moving finger writes, and having writ. . .”

From this reference (of the old poem “The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam”), the story evolves into a metafictional commentary, where the characters have the growing realization that perhaps they are characters in a story; a “bad story” not worth turning into a novel.

Even without the metafictional turn, the non-scientist characters seem to embody a feeling of frivolousness. They are attempting to distract themselves from an ongoing political crisis that threatens their existence, a task made harder by their shared secular viewpoint (the conservative Burkhardt refers to an Author, but that’s as far as he’ll go). Cogswell isn’t frivolous, but as an individual scientist–a cog in the machine, say–he realizes he has little power over the military/science conglomeration that seems to be ushering in nuclear war. This seems at odds with the individual heroism seen in “The Star Beast” and the Flandry series; perhaps Anderson was vacillating in his views of individual versus collective action during these years.

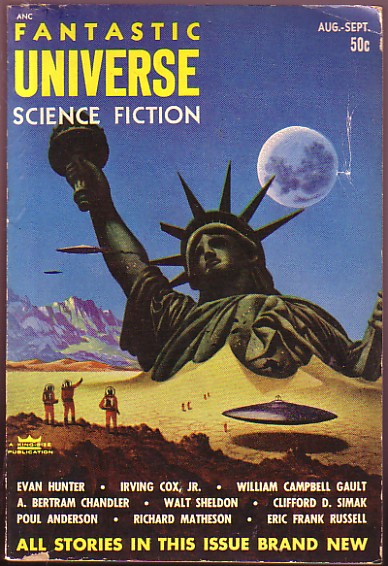

Another interesting aspect of this act of self-deprecation is the fact that it was published in Fantastic Universe. Its editor at the time, Sam Merwin Jr. (1910-1996), seems to have had relatively high standards in the early 1950s, and had a keen awareness of the stereotypes populating genre fiction. While he never had the strongest reputation as an author, his perspective might be worth looking into.

“Among Thieves” (1957)

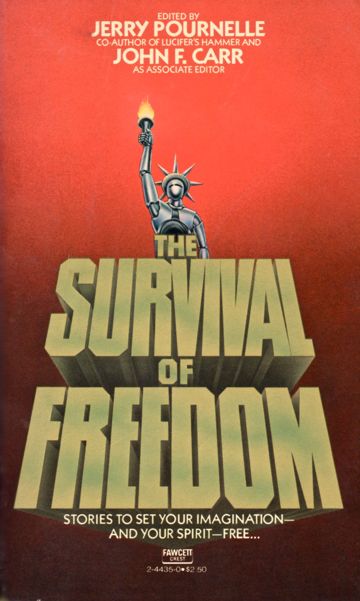

Too bad the board game Diplomacy was invented in 1959. Otherwise, I could have claimed that Anderson might have been inspired by it when writing “Among Thieves.” It’s a military drama that has drawn the admiration of Jerry Pournelle, who has anthologized it twice, first in The Survival of Freedom.

In this article, I’ve judged “The Star Beast” and “The Disintegrating Sky” to be tales without much optimism. It is difficult to find much hope in stories about the prospect of nuclear war, but their casts of characters lack someone to take on the individual burden–tremendous that that burden would be–to save the civilization from destruction. “Among Thieves” also begins with Earth in trouble, but this time there is someone willing to seriously try saving it, albeit at a severe cost.

The story begins with a scene very familiar to Anderson readers. A ranking ambassador of the Terrestrial Federation, the center of a sprawling interstellar empire, is visiting a frontier colony world. He is waiting at the negotiation table for the local head of state, Hans Rusch, Margrave of Drakenstane, who is blatantly tardy:

In the bleakly clock-bound society a short delay was bad manners, even if it was unintentional. But if you kept a man of rank cooling his heels for an entire sixty minutes, you offered him an unforgivable insult. Rusch was a barbarian, but he was too canny to humiliate Earth’s representative without reason.

Which bore out everything that Terrestrial Intelligence had discovered. From a drunken junior officer, weeping in his cups because Old Earth, Civilization, was going to be attacked and the campus where he had once learned and loved would be scorched to ruins by his fire guns–to the battle plans and annotations thereon, which six men had died to smuggle out of the Royal War College–and now, this degradation of the ambassador himself–everything fitted.

The Margrave of Drakenstrane had sold out Civilization.

Civilization had been neglecting Drakenstrane (actually, the two-planet system of Norstad-Osterik it dominates) for many years, while it struggled for survival in a drawn-out war with an adjacent colonial planet, Kolresh. Kolresh was also an imperial colony at some point, but the people there had been so isolated for so long, that they had mutated into an entirely different species. Or so it was thought. The ties between Civilization and the two warring planets have been neglected for centuries, with the depths of the biological and cultural divide being incompletely understood.

The Margrave Rusch has arranged a cease-fire in the war against Kolresh, maintaining a stalemate and acknowledge a mutual resentment toward Earth. Their rumored alliance has alarmed some of the Terrans, since the navy of Kolresh is too strong for their planet’s defenses, and had only been held at bay by the elite soldiers of Drakenstrane. Presently, Rusch invited the Terran ambassador to make a counter-alliance, supporting him with enough resources to defeat Kolresh once and for all.

Playing both sides against each other may have put Rusch in a position of influence among heads of state, but it has started to cost him domestic support. The people under his charge, most of all Queen Igra, find this prospective relationship detestable. Making an alliance with Kolresh would put Norstad-Osterik in a position to overthrow the decadent empire of Terra, or so he claims to her:

A wind sighed over the slow thunder on the beach. A line of sea birds crossed the sky, thin and black against glowing bronze.

“I know,” said Ingra. “I know the history, and I know what you’re leading up to. Kolresh will furnish transportation and naval escort; Norstad-Ostarik will furnish men. Between us, we may be able to take Earth.”

“We will,” said Rusch flatly. “Earth has grown plump and lazy. She can’t possibly rearm enough in a few months to stop such a combination.”

“And all the galaxy will spit on our name.”

“All the galaxy will lie open to conquest, once Earth has fallen.”

“How long do you think we would last, riding the Kolresh tiger?”

Tigers keep appearing in Anderson’s fiction: twice in this collection, in “Tiger by the Tail,” the first (by publication date) Flandry story, and with the tiger-human hybrid creatures of his 1974 novel Fire Time.** Aside from that, “Among Thieves” is very much a story unto itself, and Anderson does not seem to be relying on literary allusions to make his points this time. Conversations are also given more context and setting, and the relatively sparse action is not as glaring. These changes could signal his development as a writer, or having submitted this work to a different editor: John W. Campbell of Astounding.

Of course, the title of this story is taken from the old proverb:

There is honor among thieves.

Or, is it:

There is no honor among thieves.

Anderson cleverly leaves the critical beginning out of his title, so you will have to read the story to find out. That is, if Rusch’s intentions are to be considered, in the end, honorable–he thinks he can end the civil war that plagues his people, or he can attempt to spare Earth from invasion. Either way, he makes his decisions on a different moral plane than that of the crown of Norstad-Osterik or the Terran bureaucracy (although the ambassador does have a firm grasp of the situation).

Strangers from Earth contains some interesting examples of what Anderson was capable of in the 1950s, and what ideas occupied his thinking. Certainly, the threat of nuclear war and the world powers’ inability to contain it as a psychological menace is felt in his writing. There is also a belief in the individual as the agent of progress (or in many cases, preservation) for Civilization. Maybe Anderson is known today as a “hard SF” writer who followed the model of the early Heinlein, but these stories show a literary figure whose ambitions went well beyond those labels. 7/10.

* Note that this lack of sophistication, while disastrous in “The Star Beast,” was not insurmountable in Anderson’s comic tale of knights vs. alien invaders The High Crusade. Of course, that was a pre-technological civilization, and the Earthlings were made of more resilient stuff.

** Fire Time was also heavily influenced by the world-building of Hal Clement.

Anderson was fascinated by civil wars. Being raised in Texas, he probably heard a lot about them.

I’ve liked almost everything of his I’ve read, though I did have a recent disappointment–he wrote a Conan (the barbarian) novel (don’t ask me how that happened, I’m guessing money). I tried to read it, and had to start skimming–just too hard to get through. I was intrigued because it was set in the period right after Conan meets Belit, and it’s in Stygia, and that all seemed like ripe territory, but in spite of being several times the writer Robert E. Howard was, he just couldn’t make it work.

He was not the kind of writer who could ride somebody else’s tiger.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also read that one several years back, and it seems I didn’t rate it highly, as well. I don’t know if that was because of the genre or because the story didn’t seem to match the energy of the best of Howard’s stories.

By “the best of Howard’s stories,” I’m referring to “The Black Stone” from the Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos anthology, which I read as a teenager. It also was anthologized by Library of America. I don’t think I’ve come across any Conan story (or Cthulhu one, for that matter), by Howard or anyone else, that could match that one. Lovecraft’s “The Thing on the Doorstep” was surprisingly funny, however.

This time around, I’m sticking with Anderson’s SF. There’s a uniformity to how his space novels were packaged by Signet, Baen, etc., but I see now that they have a lot of different ideas and characters.

LikeLike