As explained recently, I maintain an interest in Frank Herbert’s non-Dune books. Not only do we see many of his Dune ideas and inspirations in other forms, but we can also see that his ambitions as a writer extended well beyond his signature series.

Soul Catcher (1972) is Herbert’s effort to break into mainstream literary fiction. It tells the story of Charles Hobuhet, a Native American of a Northwestern tribe, who abducts but then bonds with the thirteen year-old son of an important government official. It is an adventure saga suffused with religious, philosophical and psychological themes. I became interested in SC after reading Bormgans’ generously thorough review on his blog Weighing a Pig Doesn’t Fatten It. I definitely recommend following the link, and my article is meant to be a companion piece to Bormgans’, hopefully with minimal overlap.

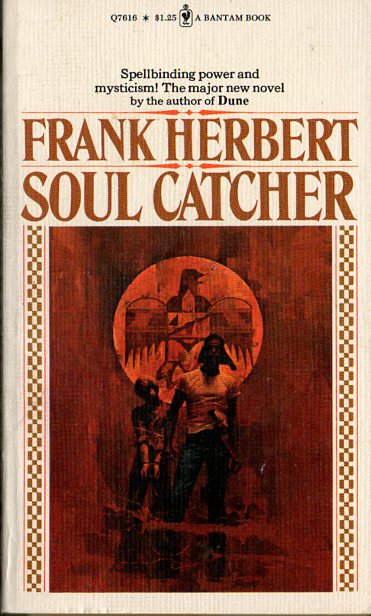

Fred Pfeiffer cover for Bantam. isfdb.org.

SC begins with Charles, a gifted graduate student, discovering a new identity for himself in the wilderness. This is soon after his young sister committed suicide, after being raped by a group of drunk loggers. Herbert suggests that Charles has been hearing voices in his head recently, which he attributes to natural spirits summoning him. An encounter with a bee leads to a revelation:

Cold came with the bee, too. It was a special cold that put ice in the soul.

Still Charlie Hobuhet’s soul then.

But he had performed the ancient ritual with twigs and string and bits of bone. The ice from the bee told him he must take a name. Unless he took a name immediately, he stood in peril of losing both souls, the soul in his body and the soul that went high or low with his true being.

This concept of two parts to the soul is also known to Western philosophy, mainly through the arguments made by Nietzsche. In his Beyond Good and Evil (sec. 12), we find the famous German thundering away at the Cartesian tradition:

. . . one must also, first of all, give the finishing stroke to that other and more calamitous atomism which Christianity has taught best and longest, the soul atomism. Let it be permitted to designate by this expression the belief which regards the soul as something indestructible, eternal, and indivisible, as a monad, as an atomon: this belief ought to be expelled from science!

In the middle of SC, Charles (now Katsuk) echoes this sentiment to David, whom he has been referring to as hoquat:

[Katsuk:] “Your dream told you that you aren’t yet ready.”

[David:] “Ready for what?”

“To go anywhere.”

“Oh.” Silence, then: “That dream scared me.”

“Ahhh, you see — the hoquat science doesn’t liberate you from the terror of the gods.”

“Do you really believe in that stuff, Katsuk?”

His voice low and tense, Katsuk said: “Listen to me! Every person has two souls. One remains in the body. The other travels high or low. It is guided by the kind of life you lead. The soul that travels must have a guide: a spirit or a god.”

“That isn’t what they teach in church.”

Katsuk has found his guide in the spirit Raven, and throughout the book he interprets the behavior of a flock of — actually, a conspiracy of — ravens as the actions of a supernatural being in alliance. If these blackbirds were actually crows, they would be a murder, hewing even closer to Katsuk’s intentions.

Katsuk’s mission, as revealed in the opening of the novel, is to take David away from an upscale wilderness camp (where he was working as a councillor), educate him in his naturist religion, and kill him as part of a sacred ceremony. Just like the birds, Katsuk interprets David’s actions as signals of a soul in transformation. David must complete his spiritual journey as someone willing to be sacrificed for Katsuk’s “message.”

As their friendship develops, Katsuk and David both have their struggles with competing motivational drives. Katsuk wants to use David for revenge against the society that took away his younger sister, but he also cares for his well-being and growth. David knows he must escape from Katsuk, but thrives under his guidance. In each person, one of these drives will ultimately win over the others, as anticipated by Nietzsche:

But anyone who considers the basic drives of man to see to what extent they may have been at play just here as inspiring spirits (or demons and kobolds) will find that all of them have done philosophy at some time — and that every single one of them would like only too well to represent just itself as the ultimate purpose of existence and the legitimate master of all the other drives. For every drive wants to be master — and it attempts to philosophize in that spirit.

— Beyond Good and Evil, sec. 6

SC is dedicated to Ralph and Irene Slattery, a married couple who were each highly-regarded clinical psychologists in California. They were friends with Herbert and gave him many insights into human motivation. Irene was a student of Carl Jung in Zurich, and fled Europe soon after witnessing the rise of Hitler in person. She translated her notes from Jung’s lectures for an eager Herbert, and impressed upon him many ideas over time – not only the Jungian understanding of racial memories and the subconscious, but (from experiencing Hitler) the dangers posed by emergent national heroes.

I’ve read some discussion of SC claiming, with good reason, that the most important theme of the book is that of innocence; I tend to think of David’s repeated identification as “the innocent” as a plot device, rather than the key to a principal abstract theme. The real purpose of utilizing this young character is to facilitate a serious attempt to connect with the reader’s subconscious.

- Katsuk’s revelations are often occurring subconsciously, as he is waking for sleep or in a trance-like state. The encounter with the bee is the first incident, but other messages come to him as he is deeply ill, and while constructing a bow out of driftwood. Some of the descriptions of the spirit world that Katsuk visits have been criticized as inaccurate to traditional Quileute beliefs, but Charles became Katsuk very rapidly — and therefore, imperfectly — and neither his visions nor his actions should be construed as representative of Quileute Indians in general.

- SC includes detailed descriptions of David’s dreams and waking moments, beginning with the morning he leaves for camp. Sentences like “without opening his eyes, he could sense the world around his home — the long, sloping lawns, the carefully tended shrubs and flowers” seem odd at first, but Herbert pursues the subconscious throughout the book.

- David’s youthful perspective is intended to invoke our own memories of childhood experiences. Herbert can overplay the naiveté sometimes, such as when David confuses the ethnicity of his South Asian housemaid with the Northwest Indians of his own state of Washington, but for the most part he describes a plausible young person. The dialogue between David and Katsuk is significantly better than the conservations between the submarine crew of The Dragon in the Sea.

Why do this? Herbert was an enthusiastic fan of Jung’s ideas, and the relative simplicity of this novel offered the opportunity to attempt the ambitious trick. SC (like almost every other novel I’ve read) is appreciably simpler than Dune, and Herbert kept the cast of characters minimal, the setting richly described but simple, and the plot moving in a single direction. Most of the time, the two characters follow a single path through the wilderness, and deviations from it are consistently thwarted.

The novel is effective at building suspense right to the last pages. Will Katsuk follow through on his promise to kill David, after befriending him and teaching him so much? I won’t spoil it here. On the surface, Katsuk’s final actions appeared triggered by a misunderstanding, but throughout SC he has been ascribing intentions on practically everything he observes around him, accidental or not. Once again, the boundary between religious enlightenment and insanity is blurred.

SC was a very important effort in the career of Frank Herbert, and its origins were described in the biography Dreamer of Dune. After completing the entire manuscript in 1971, Herbert spent some days thinking things over before mailing, at one point attending a local seminar organized by Native Americans. After experiencing the outrage first-hand — I admit to have known very little about these issues, at least in the Pacific Northwest, until reading SC — he rewrote the entire novel and replaced the ending. This new conclusion was met with strong disagreement from an influential friend of his, a Quileute Indian, but it received critical praise from the likes of Dee Brown (who wrote Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee).

A small Seattle outfit wanted to make a movie out of SC, but only if Herbert would allow them to change the controversial ending. Herbert refused to allow this, and the film was never made. Bormgans mentions another planned adaptation of SC, which also would have a changed ending. My feeling towards this, and screen adaptations in general, is that there needs to be a monetary return on some level and I’m not going to get upset about something I could just opt not to see.*

Also interesting is the fact that an executive at Putnam wanted Herbert to increase the size of his submitted manuscript, so the author added about 30 pages of additional material. Dreamer of Dune does not reveal what part of SC was added in at this stage. It’s tempting to think that it was the sheriff’s quotes of epitaphs drawn from Charlie’s writings, as they regularly appear throughout the book without changing the plot. But the Dune series demonstrated how much Herbert made use of fictional quotations to deepen his philosophical themes.

My guess that the added section is the reunion Katsuk has with some members of his tribe inside the wilderness, with David in tow. It includes a disturbing interaction between Charlie’s ex-girlfriend and David, something that Herbert may have hesitated to include when submitting the original manuscript. He may have felt emboldened my a second chance to add a controversial passage like that (sometimes, that’s how I manage to push through some of my engineering ideas).

Soul Catcher is an emotional, controversial and challenging book. Herbert has once again managed to package several themes together using his unorthodox style. It is an easier book to get into than Dune, to the point where I would easily recommend it for non-SF readers who aren’t obsessed with political correctness. The contention is the goal. 8/10.

* That said, I was deeply disappointed in the way Amazon Studios shoehorned its own politics into several short stories by Philip K. Dick.

Available for Kindle now, maybe I’ll try it sometime.

Here’s the thing–there are real Indians. (It’s the generic word most of them use for themselves, to this very day, because they never had a word to refer to all tribes before the Europeans came–how could they, with so many different languages?) They have real goals, real problems, and they are all very different from each other. Many are in fact western people now, with no more than a self-conscious memory of how their ancestors used to see the world–it would be impossible for them to live completely in that way. They are different, but in the same way immigrants and their children who live in a tight community here are different. They maintain a sense of ethnic consciousness, which is something that should be respected–no more or less than anyone else’s ethnic consciousness.

And there is the Indian of western consciousness, European consciousness, who is more of a philosophical construct meant to express disquiets about our civilization than anything else. All variations on what Rousseau wrote about noble savages, and what Rousseau wrote was nonsense. They weren’t savages, and they weren’t noble. They were just trying to survive as best they could, with the tools they had to hand.

Underying all that is the guilt we felt about taking the land away from them. But like the Dr. John song says “If I don’t do it, somebody else will.” The mere existence of technological civilization created the certainty that the Americas would be wrested from their original settlers. As indeed they had wrested it from each other for thousands of years. It wasn’t Eden, unless you mean an Eden populated mainly by Cains.

We idealize them to try and make up for the fact that came here mainly as Christians, and Christianity says treat others as you would be treated, and no sane person could ever say we lived up to that, but we mainly hadn’t done so to ourselves either, so that tracks. But once they were no longer a threat–once they’d been conclusively defeated and subjugated–it become possible to romanticize them. (The existence of Indian Casinos–that most Native Americans don’t profit from–has somewhat damaged that image.)

The Golden Rule exists in many cultures, but it’s an almost impossible rule for hunter-gatherers to follow. All humans are tribal, to some extent. And all humans kill other humans in reponse to certain material and emotional pressures–even though some individuals may break with that norm. Humans have a long history of murder and thievery, and that was true here before any white person saw the land they came to call America (that was largely based on a misunderstanding as well).

Herbert had perhaps been partly influenced by native people in the Pacific Northwest in his creation of the Fremen, but the great thing about SF is that you can create your own cultures, which have no independent existence. They are an ideal way of expressing your ideas, because they belong to you–as real people never can. You don’t end up telling other people who really exist who they are, and what they’d do in such a such situation. Which of course would vary from individual to individual anyway. Herbert’s friend should have known that there is no one way such a person would behave. But I can empathize with his feeling that only somebody of that heritage should have the right to show negative behavior.

(I can also understand his real objection–that a famous writer is using one man to symbolize his entire tribe, arguably all of the surviving American tribes–so whatever he does, all of them do. Another problem with writing about a real culture you don’t belong to. But it could be argued that the only way to avoid this problem is to never write about the world around you, which is full of cultures you don’t belong to. Or to just write as if only the culture you come from is real.)

I would say all Herbert had to do, to make his points, would have been to write a science fiction novel, and the Indian would be the native of a colonized planet, conquered by humans. And more people would have read it, and more people would have understood his point, without politics and PC getting in the way, but then he’d still be “Just a science fiction author.” The endless quest for status. And to break out of a niche, and all genre authors try this at some point, no matter how successful. Sometimes it works.

I googled around until I found the ending (in Herbert’s biography, written by his son). I can see why his Quileute friend was upset. Probably none of the Pre-Columbian Quileute would have been–they told far bloodier stories, and felt no guilt over it. The New Agey western image of the first settlers here has been so pervasive that it’s become part of how they see themselves. Probably the main critique a Quileute from centuries before would have had would be “What took him so long?” They didn’t have the luxury of sentiment.

(If I romanticized them, which I try not to, it would be in a different way–I’d imagine them more like Westlake’s Parker–the way humans used to be, more like wolves, identifying with wolves, and there is some truth in that, but they were never that Stark–they told stories, they wrote songs, they had art, they created religions, and they had conflicts, between the lives they led, and the way they sensed life could be, if they were not such flawed creatures–like all humans–perhaps fewer conflicts than ‘civilized’ men. Not a lot fewer. Not even life lived at the edge of subsistence is all that simple. It just seems so, in retrospect. If we were living that way, we’d be nostalgic for what we have now. Or so I imagine. Hey, maybe we’ll get to find out.)

I know of a much simpler and far less cuddly version of this story. I read it in an anthology of adventure stories (for young readers, if you’d believe it). I can’t remember the title, or the author, and it was so long ago. Google has not helped me find it.

On a colonized island, a red-bearded man, one of the dregs of his culture, degraded and lost, is drinking himself to death. A native (I don’t know what tribe, and it doesn’t matter) sees him, and strikes up a sort of friendship. One night he abducts the man, and they go on a journey together, in an outrigger canoe, face many dangers–there is no question that the native is the stronger and more resolute of the two by far. In this world, he is the superior race. But deprived of alcohol, exposed to the clean ocean air, the red-bearded man gradually comes back to himself, thrives under adversity, grows strong, clean, alive again.

Full of joy for his redemption, he turns to the native, who has done him this great kindness and tries to express his gratitude–asks what he can give him in recompense. Speaking in the pidjin English he knows, the native says, smiling, “Me like that head you have.”

He never had any love for the red-bearded man. His interest was purely aesthetic. He wanted him in good condition, so he could bring back a unique trophy to his people, that will grant him special status. No redheads among his people.

The man is shocked–then he laughs–spreading his arms open to the world, he shouts “Take it, you fool! It’s cheap at the price!”

I think that about sums it up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One more thing–do you really think that whatever the hell Nietzsche was talking about corresponds in any way with Native American ideas of the soul? What the hell would he know about that? Nietzsche was a strong critic of Rousseau–I would suggest that was the child rebelling against the parent (as Marx rebelled against Hegel). At bottom, they came from the same basic school of western thought. The good old ‘grass is greener’ school.

LikeLike

Nietzsche skepticism about the “soul atomism” is clearly reiterated by Charles, so I think that’s shared – at least, in the way Herbert writes about it. Herbert also spends a lot of effort showing how Katsuk is not an accurate embodiment of pre-Columbian Quileute beliefs, without explicitly saying it.

As to what Nietzsche tried to replace the atomic soul with, well that’s a different issue. It’s a lot easier to understand how he tears concepts down, than how he builds them up. Although to his credit, Nietzsche does not claim to be the first one to think of the human soul as multifaceted and divisible. He points out that Plato had the idea, or was at least receptive to it, or the soul being composed of smaller, interconnected components.That’s as far as I’m going to go on this particular topic.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Eh, sorry – that last comment didn’t end the way I’d like. I’m a little frustrated by my particular edition of Beyond Good and Evil – it’s the Kaufmann translation – not by any questions lobbed my way about Nietzsche.

I don’t want to be in a position of defending Nietzsche too much, since I haven’t absorbed enough of his books. Herbert wasn’t exactly a Nietzsche acolyte either … I think Children of Dune made that pretty clear. He made good use of pieces of Nietzsche’s philosophy, and combined them with those of Jung and others, including his own, to write his books.

I’m even less in Jung’s corner than Nietzsche’s, I suppose, due to my years working in a Psychology Department. But I think Herbert bought into Jung to a greater degree than he did Nietzsche.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The soul is just the life essence of a living creature. I don’t know if it outlives that creature. I don’t know how many parts it has, or whether it’s divisible or not. I know it exists, and is not a mere philosophical construct, because I’ve seen it in the eyes of dogs, and dogs don’t have philosophy.

I do know the aboriginal inhabitants of this continent never heard of Nietzsche, and he knew nothing about them.

I understand, of course, that Herbert had read Nietzsche. I think my issues with Mr. N. have been sufficiently explored elsewhere. The fact that people keep disagreeing about what he meant–to the point where he was the central influence on Naziism, while at the same time referred to as somebody who would have hated the Nazis–makes the point that he was sufficiently ambiguous to make it impossible to be sure what the hell he meant. 😉

LikeLike

NOTE: this is a response to the first comment. It just ended up in the wrong place.

Adventure stories definitely had a different flavor to them in the past.

You bring up a distinction that I probably could have done more with – Charles is emulating the pre-Columbian version of his People. He spends the whole book in a loincloth and moccasins (something covered up by the Pfeiffer cover). When he meets up with other Quileutes, they are clearly troubled by the path he’s taken, and the consequences that they will have to deal with. They are contemporary people, stuck between a violently disturbed family member and their employers, outside friends, etc., not to mention the law and the public at large.

LikeLike

It is an important distinction–he’s trying to recreate something he’s already lost, that he can never really get back. He should not be seen as a representative of his people, and Herbert was right to make that clear. However, because he’s one of the two central characters in the book, and the other one is white, that’s how he’s going to be seen anyway.

And I should probably read the book before stating any opinion about it. Let’s just say I’m stating opinions about the issues relating to the book. And I have done some reading in that area. And a lot of very conflicted thinking.

I once saw an Indian–possibly a Shinnecock–praying near dawn, at Montauk Point.

I was there bird-watching, and I left immediately, feeling like I was intruding. Because I was.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope you do read Soul Catcher some day, for this reason – I mentioned above how Katsuk interprets the behavior of ravens (or crows) as the willing assistance of the spirit Raven. But could the birds’ actions, and timing of those actions, explicable by natural corvid behavior? Crows and jays would definitely pick up on the patterns in the actions of hikers and hunters in the wilderness, and what the humans might leave behind. . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ravens and other corvids will absolutely observe the actions of other creatures, exploit them. They learn to utilize humans as sources of food, and I’ve long suspected that crows or jays, having located an owl taking shelter in a tree, will intentionally try to draw the attention of humans towards the owl, hoping the owl will flush from the tree, making it easier for them to harass it. They also use us for entertainment. Greater intelligence means a greater capacity for boredom.

And if you explained all this to Katsuk, what would it prove? Raven is acting in accordance to Raven’s nature. That nature is assisting him. Honestly, in his situation, in his state of mind, I’d interpret it the same way.

LikeLike

I’m not so sure Herbert was trying to “break out” of the SF genre with Soul Catcher. He applied for a government grant to write it in 1968, and in 1971 he had some success with Dune – but it wasn’t yet the massive phenomenon of later years. Dune wasn’t really in the bookstores at the time, so it’s hard to say that Herbert had achieved any kind of popular fame at that point.

Was he chasing prestige with a mainstream novel? Maybe – SF seems to be a ghetto in the literary world, more so then than now. But judging what I read from his biography (Herbert was clearly a brilliant and very unusual man), I’m not convinced that he was chasing ‘status’ as much as a sustainable way to provide for himself and his family.

I do concede that this argument is easier to make after Soul Catcher, than, say, in a review of something like “The Eyes of Heisenberg.”

LikeLike

In any professional storyteller, there are differing needs–the need to support oneself and ones family–the need to express yourself in a way that ordinary non-fiction prose, scientific or philosophical, will never succeed in doing–and the need to be recognized as an individual voice, not just an expression of a certain established form. Even if you love that form. You still want people to see you. What you care about, that makes you different from everybody else.

And Herbert was very different from everybody else in his field–whether it was SF, or literature at large.

LikeLike

Certainly, we can see the “money matters” in genre fiction, like SF or the Hard Case Crime reprints. At this point, having read 7 of his books, I’d imagine Herbert would have a tougher time _not_ writing in his own individual style. Much easier to include ideas that John W. Campbell liked (e.g. the remote stress-meter in The Dragon in the Sea, although Herbert was also a fan of analog “mind-reading” devices, and often hooked his own kids up to a WWII-era lie detector).

One consequence of Herbert’s unusual nature was owing money to the IRS, so even if his books sold well the pressure to publish again must have been there. I skipped around the Dreamer of Dune biography, figuring I’ll return to it when the next Herbert book turns up at the top of my pile, and consider what the incentives might have been at the time. He certainly had a lot of confidence that “Soul Catcher” was going to do well.

LikeLike